The piano was my first instrument and it will always reside deep in my heart. My earliest childhood memories are me at like 4 years old sitting at the piano in our living room playing out some inner narrative about wild animals. As a teen it was evident that I was going to pursue a life as a musician and composer. My parents responded to my obsessive focus by urging me to develop something that I could “fall back on” in case things didn’t work out. They suggested that I take an apprenticeship with a piano tuner and rebuilder. I agreed. I had a sense that it would be good to learn more about the inner workings of my principal instrument. It turned out to be quite an important endeavor. It did help pay my way through school and to live for a several years. But it became something much more.

In early 1970s at the conservatory in Toronto I was hearing and learning about contemporary classical music, including some highly innovative music created by composers like Henry Cowell and John Cage. Cowell was playing on the inside of the piano – strumming, plucking and scraping the strings; Cage developed this technique called prepared piano, which involved placing various objects in between the strings inside the piano to make different kinds of sounds and resonances. These composers and others were seeking new sonic dimensions to extend the musical “language” of the time. I was fascinated by these ideas, and it intersected with my work inside pianos.

Unfortunately, pursuing the potential for a new sonic universe was impeded by a mechanism that wasn’t designed to enable its execution:

- It took a long time to prepare instruments for performance, and music scores often included several pages of instructions;

- Many venues refused to let you mess with their beautiful concert instruments. Touching the strings can rust them, and placing objects between strings would put the piano out of tune;

- Even if they let you do it, you would need a second instrument to perform anything else on a concert.

Like much of what was going on in the contemporary classical musical world of the era, this all lived in a very esoteric and limited musical world.

In studying about the development of the piano, I learned that it took over 100 years to develop into the piano we use today, and the designers were building upon an existing foundation of instruments like the harpsicord; and I found out that no significant new design developments have taken place in over 100 years.

I wondered – what if we were able to extend the instrument to accommodate some of these new ideas? It might take another 100 years, but it would be an amazing instrument.

Why not? There is a long history of collaboration between composers and instrument designers. Beethoven wanted a bigger sound and larger range to create the music in his head. Liszt needed quick action response to realize his vision. I figured that my knowledge of the inner mechanism would enrich my exploration of this musical material and inform the design.

I starting working on some design concepts that would extend the current action and body of the instrument –

- action enhancements that would activate different harmonics or components of the sound;

- hammer options to strike the strings with different kinds of mallets;

- a flexible sound board box that would enrich the sound resonance and change the sound as it unfolds.

The possibilities were invigorating. The experiments were illuminating. At one point I had 9 instruments in my modest country home outside of Toronto, including one in the kitchen. I was not popular at home for this initiative.

It didn’t take long for me to realize that I didn’t have the expertise to do this myself. I would need a major piano manufacturing company and a great deal of money and time to accomplish the task. I would need this to be the focus of my life, and my real interest was in composition and music making.

This realization was a bit discouraging, but these musical interests drove me to find another way to realize the vision. In the late 1970s there were amazing developments taking place in the field of computer music, and I went to Eastman School of Music to learn about it. Eastman is a premiere music conservatory, and at that time it was the only conservatory in North America to implement a computer music program. Significant work was taking place in engineering and computer science institutions like MIT, Stanford and the University of Toronto. But Eastman was a community of some of the best musicians in the world, and that’s where I wanted to be.

It was a highly experimental terrain, and it was an exciting time to be involved. Back then we worked on mini-computers – large standalone machines that were kept in refrigerated rooms. We worked in what was called “non-real time,” an intriguing concept. What it meant was that we had to program our musical ideas using various software systems, and the computer had to churn away to calculate the results, sometimes for hours or even days. There was no traditional “instrument” that you could write for or practice on in the traditional sense.

Musically it differs from traditional acoustic instruments because there are no “inherent” musical properties –

- no membranes, reeds, strings or tubes;

- no resonating box that physically defines its sonic characteristics;

- no inherent interface like a piano keyboard that guides how one controls performance.

It’s really a blank slate. You had to become an instrument designer, creating the sonic world and musical language inherent in that work, driven by our vision and imagination.

My first forays into this new world involved recording and processing piano sounds –

- Playing with harmonics;

- Exploring different kinds of attacks;

- Filtering and processing sounds;

- Layering sounds.

inDelicate Balance

In the late 1980s I composed inDelicate Balance, a computer music composition that integrates found sounds, live and manipulated piano sounds, and representations of sounds from the inner ear and internal world into a multi-movement work that offers a perspective on contemporary existence utilizing the sounds that surround us. inDelicate Balance was realized using a combination of digital software processing and mixing techniques, and “non-real time” sampling, processing, and mixing systems to render the soundscape heard by the audience through tape or computer playback through an amplification system.

The second movement of inDelicate Balance – “Somewhere between” – was created using sampled piano tones and gestures, and is an early example of my exploration of the “extended piano,” where I play with harmonics; incorporate different kinds of attacks, resonances and sound structures; filter, process and layer sounds; and explore alternative approaches to musical & compositional process.

The Red Shoes Ballet Suite

The next piece is from my Red Shoes Ballet Suite, a dance theater production by the Ballet of the Dolls based on the 1948 film The Red Shoes, directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. I composed and produced the music for the show, comprised of piano, violin and soundscapes; and I collaborated with Artistic Director/Choreographer Myron Johnson to create this production in 2001 and in 2002.

The soundscapes for The Red Shoes were created using similar “non-real time” software tools as was used for “Somewhere between,” with a focus on a collection of sampled piano gestures and musical motives. This scene – “Julian and Vicky Pas de Deux” – reflects the emerging love between Julian – the composer writing the music for the dance company’s new ballet, “The Red Shoes,” based on Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale – and Victoria Paige, the prima ballerina performing the main role in the upcoming show.

Now many years later we have come a long way towards developing digital music instruments that can accomplish in live performance what could only then be done using general purpose computers in non-real time. I am currently using a keyboard sampler (Yamaha Motif XF), a sophisticated computer with a piano keyboard user interface, and I use it to record and process sounds to use in my compositions – acoustic instruments, noise, sounds from our world.

I performed a new version of “Julian and Vicky Pas de Deux” for the Untether solo keyboard concerts at Homewood Studios in 2019, a digital “instrument” that blends a softened sampled piano sound; a plucked piano sound; a voice that enriches the post attack resonance from the plucked piano; and a voice incorporating pre-recorded phrases that are triggered on the keyboard during performance.

Passing

“Passing” is the opening movement from a multi-movement keyboard suite called GONE that I performed at the Untether solo keyboard concerts at Homewood Studios. GONE is a suite of movements originating in Off-Leash Area‘s show “Dancing on the Belly of the Beast,” a dance theatre production about adult orphanhood. This scene is an Emotion Gallery; “Passing” is about the passing of a loved one.

The instrument developed to create this piece incorporates a sampled traditional grand piano sound, a softened electric piano-like setting, a plucked piano sound, and a sound that splices off the attack of the plucked piano and enriches the post attack resonance. In “Passing” I am more deeply entering the world of “post attack resonance.”

The Legacy Project

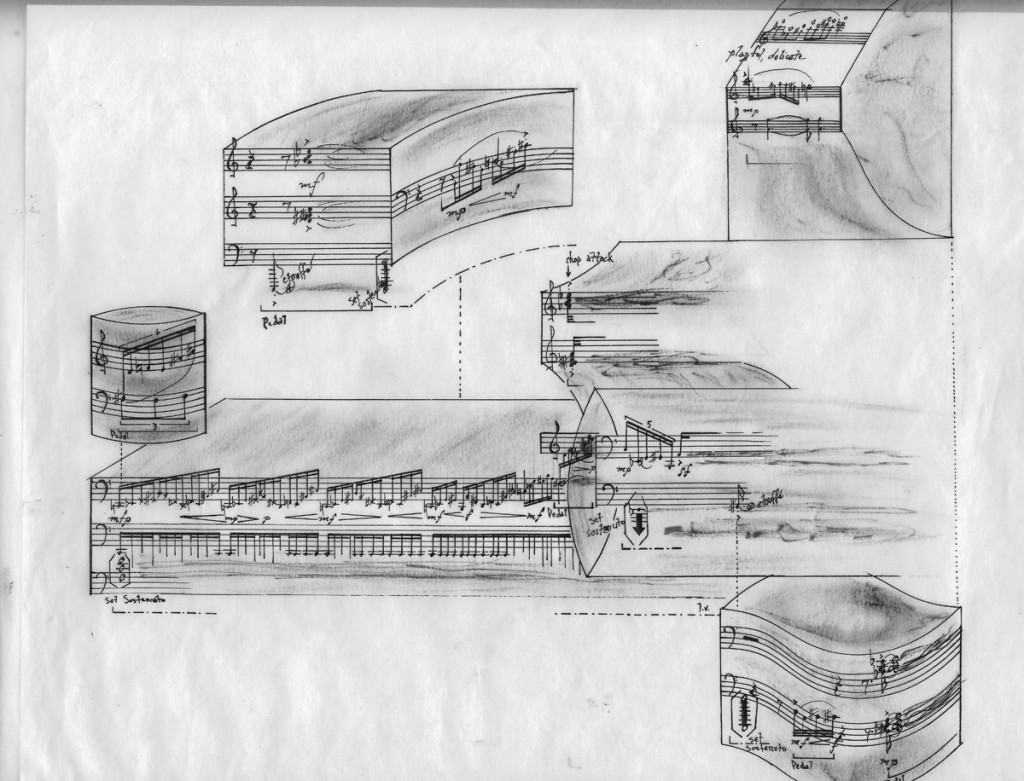

The Legacy Project is a reflection/meditation on the expression “we sow what we reap.” In The Legacy Project I continue to delve deeper into the components of the recorded and transformed piano sounds. This instrument comes closer to realizing my original vision of the transformed or extended piano, and includes the plucked piano voice; the plucked piano resonance voice; and a voice that incorporates sampling of the piano using different mallet strikes, exciting harmonics, transforming resonance, strumming and playing with sticks on the inside of the piano.

I performed the first version of Legacy – Legacy 111219 – at the fourth and final concert of the “Untether – the Homewood Studios Concert Series”:

I continued to develop compositional concept for Legacy to create a more integrated and flexible instrument. Using the instrument in this most recent form, it is easier to explore the harmonic structure of the sounds with each of the instrument’s components, blend different layers of the sonic content, and play with the nuances of individual sounds and sound complexes. Each of the sampled sounds recycle in long loops that reinforce their individual identity while creating unique interactions with the other sonic elements. When notes and layers are played together, they function as a community coming together to work in concert. In the unfolding of their reiterations they function as independent entities with individual agency – engaging with others at times serving seemingly unified activities, while at other times in apparent conflict or dissonance.

This is Legacy 21120.